Books of Hours

were popular around the 14th and 15th centuries, often

commissioned for lay people of many different backgrounds – whether middle

class or aristocracy. With the ability to personalize them, they ranged between

many different qualities in binding, script and illumination, though those

along the more expensive strain were well decorated and expensive. However, The

Book of Hours of Lorenzo de’ Medici, commissioned by Lorenzo de’ Medici himself

in the year 1485, appears to be rather exceptional, even in comparison to many

of the more intricate.

A man of great wealth

and many children, Medici was known as Lorenzo the Magnificent as a ruler and statesman,

as well as a patron of the arts. Contributing much to the artists of Florence,

he supported many artists, even giants such as Leonardo da Vinci and

Michelangelo. His choice to commission the Books of Hours of Lorenzo de’ Medici is rather unsurprising,

as is the sheer amount of detailed artistry he was willing to fund in the work.

Part of a

collection called the Libriccini delli

offitii, di donna ( or small books of the offices, for the use of the

ladies), this book was one of the five commissioned for the weddings of his

beloved daughters. His love for his daughters must have been great if the

amount beauty of these books of hours is any indication. The books even come

with the description “for the ladies,” giving the implication that the works

were meant to be small and precious treasures, much like the four Rose Quarts

and center set Lapis Lazuli on the front cover. The book itself is rather small

as well and with its 15.3 x 10.1 cm format it’s only about the size of a

postcard. Today, the original lays in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenzia in

Florence, Italy.

Part of a

collection called the Libriccini delli

offitii, di donna ( or small books of the offices, for the use of the

ladies), this book was one of the five commissioned for the weddings of his

beloved daughters. His love for his daughters must have been great if the

amount beauty of these books of hours is any indication. The books even come

with the description “for the ladies,” giving the implication that the works

were meant to be small and precious treasures, much like the four Rose Quarts

and center set Lapis Lazuli on the front cover. The book itself is rather small

as well and with its 15.3 x 10.1 cm format it’s only about the size of a

postcard. Today, the original lays in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenzia in

Florence, Italy.

Truly a work of the highest order, the jewels

themselves are not the only reason that the book is regarded as so ornate, as

the ornate silver and gold gilded biding, velvet cover and highly detailed illuminations

within look just as expensive. Lorenzo contributed much to the world of art,

and this book is no different with the sheer amount of artistry put into the

binding and pages. Engraver, illuminator, cartographer and painter Francesco

Rosselli is responsible for the work within, and covered every one of the 233

leafs within with at least an initial, adornment or frieze. In fact, the book

only appears to have had one artist and scribe working on it in its entirety,

making the detail put into the work that much more intriguing. For only one

man, the work load must have been immense, but the harmony among the art and

script was well worth the work in the eyes of many who have observed the book

of hours.

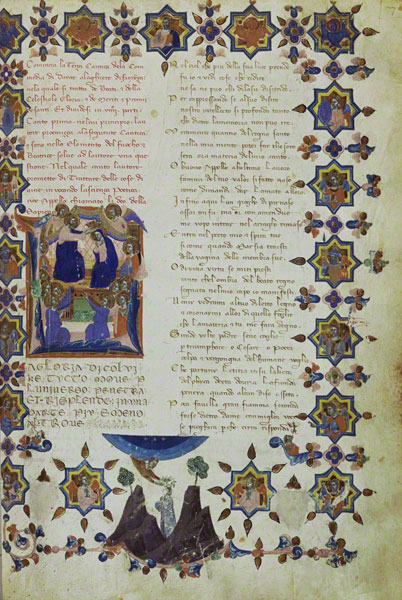

In other Books of

Hours, there were often full-page illuminations, covering as much of the page

in details, portraits and flowery intricacies as was possible. The book

contains nine total full-page illuminations like these, each complete with a

level of detail that seems to surpass many of the books of hours in the past.

Covered almost entirely in portraits and details, the illuminations swamp the

script on the pages that are the most detailed. Miniaturized portraits are

present on each of these full pages bordering the script and surrounded by

flowery details. Usually, more expensive books could have circlets where

portraits were displayed alongside the script, but Medici’s book has pages with

as many as twenty or more. The most

amazing aspect of these portraits, though, is the amount of detail put into

them. Each of them is probably no bigger than a centimeter or two, but the faces

and clothes are still prominent none the less. Even the cherubs, flowers, and

delicate details that fill in the page between the portraits are clearly

visible and distinguishable from a distance.

In other Books of

Hours, there were often full-page illuminations, covering as much of the page

in details, portraits and flowery intricacies as was possible. The book

contains nine total full-page illuminations like these, each complete with a

level of detail that seems to surpass many of the books of hours in the past.

Covered almost entirely in portraits and details, the illuminations swamp the

script on the pages that are the most detailed. Miniaturized portraits are

present on each of these full pages bordering the script and surrounded by

flowery details. Usually, more expensive books could have circlets where

portraits were displayed alongside the script, but Medici’s book has pages with

as many as twenty or more. The most

amazing aspect of these portraits, though, is the amount of detail put into

them. Each of them is probably no bigger than a centimeter or two, but the faces

and clothes are still prominent none the less. Even the cherubs, flowers, and

delicate details that fill in the page between the portraits are clearly

visible and distinguishable from a distance.

Even the pages

that don’t contain full illuminations, the work is still beautiful in its

simplicity. Historiated initials contain more portraits, the inner margins

decorated with lines of flowers and creeping details that border one side of

the page. Even by just simply changing the color of the ink on certain lines,

Rosselli was able to make even un-decorated pages look beautiful.